Elaine Vitone, PittMed, recently visited with McGowan Institute for Regenerative Medicine affiliated faculty member Ian Sigal, PhD, Assistant Professor and the founding Director of the Laboratory of Ocular Biomechanics in the University of Pittsburgh Department of Ophthalmology. There she learned about Dr. Sigal’s work and shared her experience in her article (with video), “The Forest, the Trees, and the Leaves.”

Elaine Vitone, PittMed, recently visited with McGowan Institute for Regenerative Medicine affiliated faculty member Ian Sigal, PhD, Assistant Professor and the founding Director of the Laboratory of Ocular Biomechanics in the University of Pittsburgh Department of Ophthalmology. There she learned about Dr. Sigal’s work and shared her experience in her article (with video), “The Forest, the Trees, and the Leaves.”

Over time in his research, Dr. Sigal learned that changes within the eye don’t happen in a vacuum. Hence, he studies the dynamics of the complex organ in its entirety.

Dr. Sigal notes that eyes are really, really complicated. They are full of fluid, and the amount of that fluid—and the pressure that its volume exerts—varies widely from person to person, as well as over the course of a lifetime, and even over the course of the day. The thinking, historically, was that glaucoma was the result of an excess of pressure pounding away year after year.

But as it turns out, research has revealed, plenty of healthy eyes have high pressure but never develop glaucoma.

So, Dr. Sigal’s central driving question shifted. It’s no longer about asking how nerve fibers die, or why disease happens. It’s: What is going on in healthy eyes, in all their confounding varieties?

“We don’t understand what is happening in glaucoma, because we really don’t understand the normal eye,” he says. “The most amazing thing is not that somebody loses vision. It’s that most people don’t, through our whole life. We go through so many things in our life, and this incredibly complicated, sensitive system still works.”

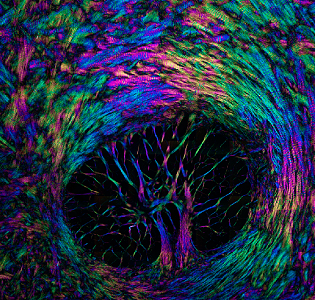

Illustration: The eye is a biomechanical wonder. A delicate balance of forces is at work every time you focus on a word or follow a line of text across a page. Fluctuating pressure pounds on the back of the eye, where the optic nerve begins; and in some people, those nerve fibers deteriorate, causing vision loss (glaucoma). Yet a certain amount of pressure is necessary for the organ to maintain its shape and function. The eye is like a soccer ball, says Dr. Sigal. “At some point, if it’s too deflated, it just doesn’t work. You can’t play.” Credit: Ian Sigal/Laboratory of Ocular Biomechanics.