The University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine and Carnegie Mellon University each have been awarded four-year contracts totaling more than $7.2 million from the U.S. Department of Defense to create an autonomous trauma care system that fits in a backpack and can treat and stabilize soldiers injured in remote locations.

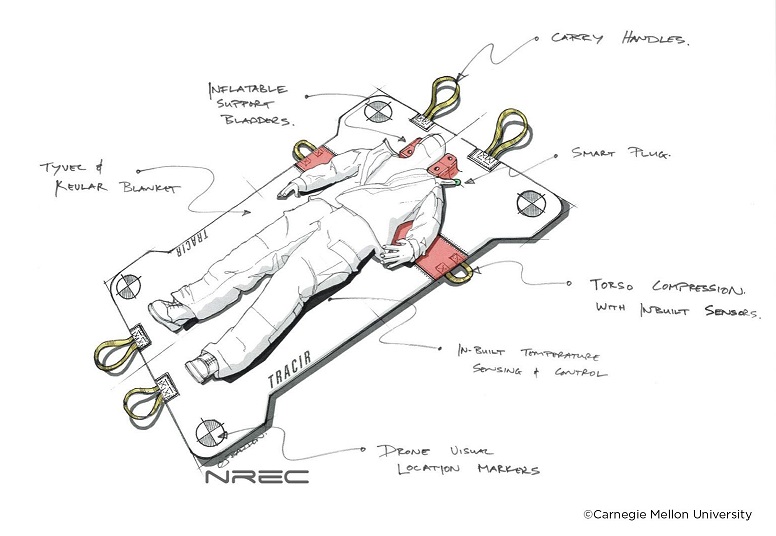

The goal of “TRAuma Care In a Rucksack: TRACIR” is to develop artificial intelligence (AI) technologies enabling medical interventions that extend the “golden hour” for treating combat casualties and ensure an injured person’s survival for long medical evacuations.

A multidisciplinary team of Pitt researchers and clinicians from emergency medicine, surgery, critical care and pulmonary fields will provide a wealth of real-world trauma data and medical algorithms that CMU roboticists and computer scientists will incorporate in the creation of a “hard and soft robotic suit” into which an injured person can be placed. Monitors embedded in the suit will assess the injury, and AI algorithms will guide the appropriate critical care interventions and robotically apply stabilizing treatments, such as intravenous fluids and medications.

McGowan Institute for Regenerative Medicine affiliated faculty member Ron Poropatich, MD, retired U.S. Army colonel, director of Pitt’s Center for Military Medicine Research and professor in Pitt’s Division of Pulmonary, Allergy and Critical Care Medicine, is overall principal investigator on the $3.71 million Pitt contract, with McGowan Institute affiliated faculty member Michael Pinsky, MD, professor in Pitt’s Department of Critical Care Medicine, as its scientific principal investigator. Artur Dubrawski, PhD, research professor at CMU’s Robotics Institute, is principal investigator on the $3.5 million CMU contract.

“Battlefields are becoming increasingly remote, making medical evacuations more difficult,” said Dr. Poropatich. “By fusing data captured from multiple sensors and applying machine learning, we are developing more predictive cardio-pulmonary resuscitation opportunities, which hopefully will conserve an injured soldier’s strength. Our goal with TRACIR is to treat and stabilize soldiers in the battlefield, even during periods of prolonged field care, when evacuation is not possible.”

Much technology still needs to be developed to enable robots to reliably and safely perform tasks, such as inserting IV needles or placing a chest tube in the field, Dr. Dubrawski said. Initially, the research will be “a series of baby steps,” demonstrating the practicality of individual components the system will eventually require.

“Everybody has a slightly different vision of what the final system will look like,” Dr. Dubrawski added. “But we see this as being an autonomous or nearly autonomous system—a backpack containing an inflatable vest or perhaps a collapsed stretcher that you might toss toward a wounded soldier. It would then open up, inflate, position itself and begin stabilizing the patient. Whatever human assistance it might need could be provided by someone without medical training.”

With a digital library of detailed physiologic data collected from more than 5,000 UPMC trauma patients, Drs. Pinsky and Dubrawski previously created algorithms that could allow a computer program to “learn” the signals that an injured patient’s health is deteriorating before damage is irreversible and tell the robotic system to administer the best treatments and therapies to save that person’s life.

“Pittsburgh has the three components you need for a project like this—world-class expertise in critical care medicine, artificial intelligence and robotics,” Dr. Dubrawski said. “That’s why Pittsburgh is unique and is the one place for this project.”

While the immediate goal of the project is to carry forward the U.S. military’s principle of “leave no man behind,” and treat soldiers on the battlefield, there are numerous potential civilian applications, said Dr. Poropatich.

“TRACIR could be deployed by drone to hikers or mountain climbers injured in the wilderness; it could be used by people in submarines or boats; it could give trauma care capabilities to rural health clinics; or be used by aid workers responding to natural disasters,” he said. “And, someday, it could even be used by astronauts on Mars.”

Illustration: Title: TRACIR. Caption: This artistic rendering shows what TRAuma Care In a Rucksack: TRACIR, an autonomous trauma care system being created by the University of Pittsburgh and Carnegie Mellon University, could look like. Credit: National Robotics Engineering Center and Carnegie Mellon University.

Read more…