August 2014 | VOL. 13, NO. 8 | www.McGowan.pitt.edu

Technology Developed by McGowan Faculty Permitted the First U.S. Implant of a Medical Device Before Lifesaving Double Lung Transplant

Based on technology developed by McGowan Institute of Regenerative Medicine faculty members William Federspiel, PhD, W.K. Whiteford professor of bioengineering, chemical engineering, and critical care medicine, and the late Brack Hattler, MD, ALung Technologies developed the Hemolung Respiratory Assist System (RAS) as a dialysis-like alternative or supplement to mechanical ventilation. Earlier this year, the Hemolung RAS was implanted into the first person in the U.S. at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC). The device was used as a bridge to transplantation upon receiving the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s approval to use the technology on a compassionate use basis.

Based on technology developed by McGowan Institute of Regenerative Medicine faculty members William Federspiel, PhD, W.K. Whiteford professor of bioengineering, chemical engineering, and critical care medicine, and the late Brack Hattler, MD, ALung Technologies developed the Hemolung Respiratory Assist System (RAS) as a dialysis-like alternative or supplement to mechanical ventilation. Earlier this year, the Hemolung RAS was implanted into the first person in the U.S. at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC). The device was used as a bridge to transplantation upon receiving the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s approval to use the technology on a compassionate use basis.

Suffering from cystic fibrosis and rejecting the transplanted lungs he had received just 2 years ago, Jon Sacker, 33, came to UPMC from his hometown in Moore, Oklahoma, as a last resort. But when his carbon dioxide levels spiked, making him too sick for another transplant, his family feared the worst.

Instead, UPMC clinicians turned to a Pittsburgh-made device called the Hemolung RAS that would filter out harmful carbon dioxide and provide healthy oxygen to his blood, giving Mr. Sacker a chance to gain enough strength to undergo a lifesaving transplant. In February, he became the first person in the U.S. to be implanted with the Hemolung RAS; in March, he underwent a double lung transplant and today is on the road to recovery.

“The entire series of events that led to this transplant and Jon’s recovery have been amazing,” said McGowan Institute for Regenerative Medicine faculty member Christian Bermudez, MD, chief of UPMC’s Division of Cardiothoracic Transplantation. “Jon had previously been very active and fit, and we knew we had to do whatever it took to help him.”

Several years before, Dr. Federspiel, director of the Medical Devices Laboratory at the McGowan Institute for Regenerative Medicine, along with a designer fabricator and a bioengineering doctoral student, developed what was known as the Paracorporeal Respiratory Assist Lung. The device underwent product development and was commercialized by ALung Technologies as the renamed Hemolung RAS. ALung was based on technology developed by Dr. Federspiel and UPMC’s former chief of lung transplant, Dr. Hattler, MD.

“We had seen the Hemolung RAS used in other countries and wanted to do whatever we could to help this patient,” said Peter M. DeComo, chairman and chief executive of ALung Technologies.

Drs. Bermudez and Crespo worked with Diana Zaldonis, MPH, BSN, in the Division of Cardiac Surgery, to notify Food and Drug Administration officials of the intent to use the Hemolung RAS, which isn’t approved for use in the U.S., and to get emergency approval from the local hospital officials. Meanwhile, Mr. DeComo drove with another ALung official in the middle of the night to Toronto, where the closest Hemolung RAS was available.

Mr. Sacker will remain in Pittsburgh for several months during his recovery, with his wife splitting her time between here and their hometown in Oklahoma. He said he’s looking forward to getting back home, where he had been a runner and public speaker spreading the word about the importance of organ donation after writing the book “Imperfect Perfection.”

“Out of all of the transplant centers we could have come to, we came here to Pittsburgh,” he said. “It’s a miracle that’s just not explainable. You just have to thank God.”

Illustration: Jon Sacker, seen here on the Hemolung RAS, came to Pittsburgh from his home in Oklahoma after rejecting his transplanted lungs and in need of a second transplant. –UPMC.

RESOURCES AT THE MCGOWAN INSTITUTE

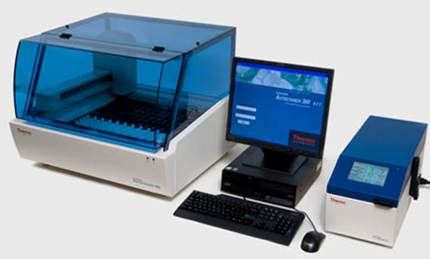

The Histology Lab Has Automated IHC Staining

Automation provides reproducible results, batch to batch staining uniformity, and fast turn-around times.

Our specialized Immunohistochemistry technician offers over 10 years of paraffin embedded antigen unmasking experience with untested antibodies yielding never before seen results.

Due to expiration dates and inventory stocks, we can offer Tunel staining and Desmin IHC staining half off our already low prices!

Contact Lori at the McGowan Core Histology Lab and ask about our staining specials. Email perezl@upmc.edu or call 412-624-5265

As always, you will receive the highest quality histology in the quickest turn-around time.

Did you know the more samples you submit to the histology lab the less you pay per sample? Contact Lori to find out how!

EVENTS

First “Regenerative Medicine Summer School” a Success

The McGowan Institute for Regenerative Medicine held its inaugural “Regenerative Medicine Summer School” the week of July 13, 2014. The Summer School week, endorsed by the Society for Biomaterials and the Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine International Society (TERMIS), was initiated and led by McGowan Institute faculty member Bryan Brown, PhD, Research Assistant Professor with the Department of Bioengineering at the University of Pittsburgh with a secondary appointment in Pitt’s Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Sciences. Dr. Brown is also the Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health Scholar (NIH K12), Magee Women’s Research Institute at the University of Pittsburgh, and an Adjunct Assistant Professor, Department of Clinical Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine at Cornell University.

The McGowan Institute for Regenerative Medicine held its inaugural “Regenerative Medicine Summer School” the week of July 13, 2014. The Summer School week, endorsed by the Society for Biomaterials and the Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine International Society (TERMIS), was initiated and led by McGowan Institute faculty member Bryan Brown, PhD, Research Assistant Professor with the Department of Bioengineering at the University of Pittsburgh with a secondary appointment in Pitt’s Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Sciences. Dr. Brown is also the Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health Scholar (NIH K12), Magee Women’s Research Institute at the University of Pittsburgh, and an Adjunct Assistant Professor, Department of Clinical Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine at Cornell University.

The Summer School week aimed at providing both international and regional undergraduate students with a hands-on learning program in regenerative medicine. The students interacted through lectures and laboratory activities with the world-class faculty members of the McGowan Institute and participated in networking and career building activities. This is the first regenerative medicine-focused summer program in the United States that is focused on undergraduates. The program is open to all undergraduates but targets students at universities where they may not be exposed to bioengineering and regenerative medicine with a goal of recruiting top students from these universities into the field. This year’s class consisted of 20 students from across the United States and internationally, many of whom come from backgrounds considered to be under-represented in the field of regenerative medicine.

Eighteen McGowan Institute for Regenerative Medicine affiliated faculty members and students participated in this very successful educational initiative.

Students toured the laboratories of William Wagner, PhD, Stephen Badylak, DVM, PhD, MD, Bryan Brown, PhD, and Thomas Gleason, PhD. In addition, they experienced an introduction to the Artificial Heart Program (Douglas Lohmann and colleagues, host) and the Center for Biological Imaging (Donna Stolz, PhD, host). The students also enjoyed an evening at Kennywood Park. See pictures of the program on the McGowan Institute for Regenerative Medicine Facebook Page.

SCIENTIFIC ADVANCES

Clinical Imaging in Regenerative Medicine

McGowan Institute for Regenerative Medicine affiliated faculty member Michel Modo, PhD, Associate Professor, Departments of Radiology and Bioengineering and the Center for the Neural Basis of Cognition, University of Pittsburgh, and his colleagues have published in Nature Biotechnology an extensive review of “clinical imaging in regenerative medicine.” The review affirms that in regenerative medicine clinical imaging is indispensable for characterizing damaged tissue and for measuring the safety and efficacy of therapy. However, the ability to track the fate and function of transplanted cells with current technologies is limited.

McGowan Institute for Regenerative Medicine affiliated faculty member Michel Modo, PhD, Associate Professor, Departments of Radiology and Bioengineering and the Center for the Neural Basis of Cognition, University of Pittsburgh, and his colleagues have published in Nature Biotechnology an extensive review of “clinical imaging in regenerative medicine.” The review affirms that in regenerative medicine clinical imaging is indispensable for characterizing damaged tissue and for measuring the safety and efficacy of therapy. However, the ability to track the fate and function of transplanted cells with current technologies is limited.

Exogenous contrast labels such as nanoparticles give a strong signal in the short term but are unreliable long term. Genetically encoded labels are good both short and long term in animals, but in the human setting they raise regulatory issues related to the safety of genomic integration and potential immunogenicity of reporter proteins. Imaging studies in brain, heart, and islets share a common set of challenges, including developing novel labeling approaches to improve detection thresholds and early delineation of toxicity and function.

Key areas for future research include addressing safety concerns associated with genetic labels and developing methods to follow cell survival, differentiation, and integration with host tissue. Imaging may bridge the gap between cell therapies and health outcomes by elucidating mechanisms of action through longitudinal monitoring.

McGowan Institute Collaborators Create Nanofibers Using Unprecedented New Method

Researchers from Carnegie Mellon University (CMU) and the University of Pittsburgh have developed a novel method for creating self-assembled protein/polymer nanostructures that are reminiscent of fibers found in living cells. The work offers a promising new way to fabricate materials for drug delivery and tissue engineering applications. The findings were published in a recent issue of Angewandte Chemie International Edition.

Researchers from Carnegie Mellon University (CMU) and the University of Pittsburgh have developed a novel method for creating self-assembled protein/polymer nanostructures that are reminiscent of fibers found in living cells. The work offers a promising new way to fabricate materials for drug delivery and tissue engineering applications. The findings were published in a recent issue of Angewandte Chemie International Edition.

McGowan Institute for Regenerative Medicine affiliated faculty members Anna C. Balazs, PhD, Distinguished Professor of Chemical Engineering and Robert v. d. Luft Professor at Pitt’s Swanson School of Engineering, and Krzysztof Matyjaszewski, PhD, the J.C. Warner Professor of Natural Sciences and University Professor of Chemistry in CMU’s Mellon College of Science, were co-authors of the paper.

“We have demonstrated that, by adding flexible linkers to protein molecules, we can form completely new types of aggregates. These aggregates can act as a structural material to which you can attach different payloads, such as drugs. In nature, this protein isn’t close to being a structural material,” said Tomasz Kowalewski, PhD, Professor of Chemistry in CMU’s Mellon College of Science.

The building blocks of the fibers are a few modified green fluorescent protein (GFP) molecules linked together using a process called click chemistry. An ordinary GFP molecule does not normally bind with other GFP molecules to form fibers. But when CMU graduate student Saadyah Averick, working under the guidance of Dr. Matyjaszewski, modified the GFP molecules and attached PEO-dialkyne linkers to them, they noticed something strange — the GFP molecules appeared to self-assemble into long fibers. Importantly, the fibers disassembled after being exposed to sound waves, and then reassembled within a few days. Systems that exhibit this type of reversible fibrous self-assembly have been long sought by scientists for use in applications such as tissue engineering, drug delivery, nanoreactors, and imaging.

The research team observed the fibers using confocal light microscopy, confirmed their assembly using dynamic light scattering, and studied their morphology using atomic force microscopy (AFM). They also observed that the fibers were fluorescent, indicating that the GFP molecules retained their 3-D structure while linked together.

To determine what processes were driving the self-assembly, Drs. Matyjaszewski and Kowalewski turned to Pitt’s Dr. Balazs, who ran a computer simulation of the GFP molecules’ self-assembly process using a technique called dissipative particle dynamics, a type of coarse-grained molecular dynamics method. The simulation confirmed the modified GFP’s tendency to form fibers and revealed that the self-assembly process was driven by the interaction of hydrophobic patches on the surfaces of individual GFP molecules. In addition, Dr. Balazs’s simulated fibers closely corresponded with what Dr. Kowalewski observed using AFM imaging.

“Our protein-polymer system gives us an atomically precise, very well-defined nanoscale building object onto which we can attach different handles in very precisely defined positions. It can be used in a way that wasn’t ever intended by biology,” Dr. Kowalewski said.

Illustration: Scientists have created nanofibers by linking modified green fluorescent protein molecules (pictured above). The nanofibers may one day be used to develop new materials for drug delivery and tissue engineering applications. –Carnegie Mellon University.

Study Suggests Cystic Fibrosis Is Two Diseases, One Doesn’t Affect Lungs

Cystic fibrosis (CF) could be considered two diseases, one that affects multiple organs including the lungs, and one that doesn’t affect the lungs at all, according to a multicenter team led by researchers at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. The research, led by co-senior investigator McGowan Institute for Regenerative Medicine affiliated faculty member David Whitcomb, MD, PhD, chief of gastroenterology, hepatology and nutrition, Pitt School of Medicine, and published online in PLOS Genetics, showed that nine variants in the gene associated with cystic fibrosis can lead to pancreatitis, sinusitis, and male infertility, but leave the lungs unharmed.

Cystic fibrosis (CF) could be considered two diseases, one that affects multiple organs including the lungs, and one that doesn’t affect the lungs at all, according to a multicenter team led by researchers at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. The research, led by co-senior investigator McGowan Institute for Regenerative Medicine affiliated faculty member David Whitcomb, MD, PhD, chief of gastroenterology, hepatology and nutrition, Pitt School of Medicine, and published online in PLOS Genetics, showed that nine variants in the gene associated with cystic fibrosis can lead to pancreatitis, sinusitis, and male infertility, but leave the lungs unharmed.

People with CF inherit from each parent a severely mutated copy of a gene called CFTR, which makes a protein that forms a channel for the movement of chloride molecules in and out of cells that produce sweat, mucus, tears, semen, and digestive enzymes, said Dr. Whitcomb. Without functional CFTR channels, secretions become thick and sticky, causing problems such as the chronic lung congestion associated with CF.

“There are other kinds of mutations of CFTR, but these were deemed to be harmless because they didn’t cause lung problems,” Dr. Whitcomb said. “We examined whether these variants could be related to disorders of the pancreas and other organs that use CFTR channels.”

Co-senior author Min Goo Lee, MD, PhD, of Yonsei University College of Medicine in Seoul, Korea, conducted careful tests of CFTR in pancreatic cell models and determined that a molecular switch inside the cell called WINK1 made CFTR channels secrete bicarbonate rather than chloride molecules.

“Pancreas cells use CFTR to secrete bicarbonate to neutralize gastric acids,” Dr. Whitcomb said. “When that doesn’t happen, the acids cause the inflammation, cyst formation, and scarring of severe pancreatitis.”

The research team found nine CFTR gene variants associated with pancreatitis after testing nearly 1,000 patients with the disease and a comparable number of healthy volunteers. They also learned that each variant could impair the WINK1 switch to prevent CFTR from becoming a bicarbonate-secreting channel.

Co-senior author McGowan Institute for Regenerative Medicine affiliated faculty member Ivet Bahar, PhD, Distinguished Professor and John K. Vries Chair of Computational Biology, Pitt School of Medicine, built a computer model of the CFTR protein’s structure and determined that all the nine variants alter the area that forms the bicarbonate transport channel, thus impairing secretion of the molecule.

“It turns out that CFTR-mediated bicarbonate transport is critical to thin mucus in the sinuses and for proper sperm function,” Dr. Whitcomb said. “When we surveyed pancreatitis patients, there was a subset who said they had problems with chronic sinusitis. Of men over 30 who said they had tried to have children and were infertile, nearly all had one of these nine CFTR mutations.”

He added that identification of the mechanisms that cause the conditions make it possible to develop treatments, as well as to launch trials to determine if medications that are used by CF patients might have some benefit for those who do not have lung disease, but who carry the other mutations.

Naturally Occurring Antibodies May Be Treatment for BK Nephropathy in Kidney Transplant Patients

A viral infection known as BK that commonly causes kidney transplant dysfunction in patients taking high doses of immunosuppressants may be treated with naturally occurring antibodies that already are widely available, according to UPMC-led research that was presented at the World Transplant Congress in San Francisco. McGowan Institute for Regenerative Medicine affiliated faculty member Ron Shapiro, MD, Professor of Surgery at the University of Pittsburgh and the Robert J. Corry Chair in Transplantation Surgery at the Thomas E. Starzl Transplantation Institute, was a collaborator on this study.

A viral infection known as BK that commonly causes kidney transplant dysfunction in patients taking high doses of immunosuppressants may be treated with naturally occurring antibodies that already are widely available, according to UPMC-led research that was presented at the World Transplant Congress in San Francisco. McGowan Institute for Regenerative Medicine affiliated faculty member Ron Shapiro, MD, Professor of Surgery at the University of Pittsburgh and the Robert J. Corry Chair in Transplantation Surgery at the Thomas E. Starzl Transplantation Institute, was a collaborator on this study.

The BK virus infects most healthy children in the U.S., but the infection is usually asymptomatic and readily cleared by the immune system. However, following natural infection, latent virus persists in the kidneys for an indefinite time because antibodies in the plasma and circulating T-cells remain at levels that are high enough to prevent virus reactivation.

“However, if the immune system is suppressed — for example by kidney transplant medications designed to prevent rejection of the organ — viral infection flares up and damages the kidney. This causes a condition called BK virus nephropathy,” said Parmjeet Randhawa, MD, a UPMC pathologist and professor of transplant pathology at the University of Pittsburgh, who led the research. “Currently, there are no anti-viral drugs or vaccines specifically designed for BK nephropathy, and none is likely to be licensed for at least the next 10 years.”

Dr. Randhawa and his team found that anti-BK antibodies are present at very high levels in immunoglobulin preparations currently being used to treat other viral infections, as well as immunologic disorders such as antibody mediated rejection of transplanted organs. These antibodies interact with a BK virus surface protein called VP-1 and effectively neutralize the virus. Such neutralized viruses can no longer infect human cells.

“By artificially constructing viruses varying in the composition of the proteins on their surface, we have shown that this neutralizing action is effective against all six common BK virus strains circulating in human populations,” Dr. Randhawa said. “These findings open the way to conduct clinical trials for preventing and treating BK nephropathy in kidney transplant patients.”

As the proposed immunoglobulin preparations are natural products derived from healthy human subjects, associated side effects are expected to be minimal, Dr. Randhawa said.

Surgical, Other Advances Improve Graft Survival of Intestinal, Multi-Visceral Transplant Patients

Innovations in surgical techniques, drugs, and immunosuppression have improved survival after intestinal and multi-visceral transplants, according to a retrospective analysis of more than 500 surgeries done at UPMC over nearly 25 years. Authors of the analysis include McGowan Institute for Regenerative Medicine affiliated faculty members George Mazariegos, MD, Director of the Hillman Center for Pediatric Transplantation at the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC and Professor of Surgery, the Jamie Lee Curtis Endowed Chair in Transplantation Surgery, with joint appointments in the Departments of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine at the University of Pittsburgh, and Abhinav Humar, MD, Clinical Director of the Thomas E. Starzl Transplantation Institute and the Chief, Division of Transplantation in the Department of Surgery at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, and a Professor in the Department of Surgery at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine.

Innovations in surgical techniques, drugs, and immunosuppression have improved survival after intestinal and multi-visceral transplants, according to a retrospective analysis of more than 500 surgeries done at UPMC over nearly 25 years. Authors of the analysis include McGowan Institute for Regenerative Medicine affiliated faculty members George Mazariegos, MD, Director of the Hillman Center for Pediatric Transplantation at the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC and Professor of Surgery, the Jamie Lee Curtis Endowed Chair in Transplantation Surgery, with joint appointments in the Departments of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine at the University of Pittsburgh, and Abhinav Humar, MD, Clinical Director of the Thomas E. Starzl Transplantation Institute and the Chief, Division of Transplantation in the Department of Surgery at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, and a Professor in the Department of Surgery at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine.

The study was led by Goutham Kumar, MD, a transplant surgery fellow at UPMC’s Thomas E. Starzl Transplantation Institute. Dr. Kumar was recognized for his work with the Young Investigator Award by the 2014 World Transplant Congress and presented his findings at the group’s July 2014 meeting in San Francisco.

“UPMC has led the way in the development of new surgical techniques and important research involving transplantation, and our analysis shows that our innovations have made a real difference to patients,” Dr. Kumar said.

The researchers examined 541 intestinal and multi-visceral transplants done at UPMC from 1990 to 2013. The total consisted of 228 pediatric transplants and 313 adult transplants; 252 were intestine-only transplants, 157 were liver-intestine, 89 were full multi-visceral, and 43 were modified multi-visceral. A majority of the pediatric patients suffered from gastroschisis, followed by volvulus and necrotizing entercolitis. The adult patients needed transplants because of thrombosis, Crohn’s disease, or some kind of obstruction.

Researchers analyzed several outcomes and found that pre-conditioning with certain immunosuppressants, the time the graft is outside of the body, certain blood types, and a disparity in the gender of donor and recipient were among the factors predicting graft survival.

The Charles E. Kaufman Foundation Awards Funds to McGowan Institute Affiliated Faculty for Scientific Studies

The Charles E. Kaufman Foundation, part of The Pittsburgh Foundation, recently announced its 2014 grants – amounting to $1.95 million – to support cutting-edge scientific research at institutions across the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

The Charles E. Kaufman Foundation, part of The Pittsburgh Foundation, recently announced its 2014 grants – amounting to $1.95 million – to support cutting-edge scientific research at institutions across the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

Under the leadership of a seven-member Board of Directors, supported by a specially-appointed seven-member Scientific Advisory Board, systems and processes have been established to administer the Kaufman Foundation’s grant making program. In this, its second series of annual grants, the organization awarded funding to five initiatives in the New Investigator Research category and four grants in the New Initiative Research category.

In the New Investigator Research category, a grant of $150,000 over 2 years ($75,000 per year) was awarded to McGowan affiliated faculty member Tzahi Cohen-Karni, PhD, Assistant Professor, Department of Biomedical Engineering, Carnegie Mellon University, for research on “The Investigation of Pancreatic Islet Electrical Properties by a High Density Nanodevices Array”

In the New Initiative Research category, a grant of $300,000 over 2 years ($150,000 per year) was awarded to Ayusman Sen, PhD, Distinguished Professor, Department of Chemistry, and McGowan affiliated faculty member Anna C. Balazs, PhD, Distinguished Professor, Department of Chemical & Petroleum Engineering, University of Pittsburgh, for research on “Autonomous Interacting Microbotic Systems”

Charles Kaufman passed away in September 2010, shortly after his 97th birthday, leaving his estate of almost $50 million to the Foundation, of which approximately $40 million was assigned to the Charles E. Kaufman Foundation to support new research initiatives at Pennsylvania institutions of higher learning in chemistry, biology, and physics. The fund is valued as one of the major resources for basic scientific research in Pennsylvania.

A former chemical engineer, Mr. Kaufman amassed most of his wealth following his retirement, all of which he dedicated to his heartfelt ambition for his philanthropy to one day help fund breakthrough scientific research and, he hoped, Nobel Prize-winners whose scientific accomplishments would contribute significantly to the betterment and understanding of human life.

“Mr. Kaufman’s vision was to use the power of research to drive innovations for humankind,” said Molly Beerman, The Pittsburgh Foundation’s Interim President and CEO. “His fund at The Pittsburgh Foundation has made great strides in reaching this lofty goal in just two short years, delivering much needed support to researchers at a time where other traditional funding sources have declined.”

“Because of the generosity and foresight of Mr. Kaufman, we are able to facilitate the initiation of research projects and cultivate new researchers, placing them in a position to deliver advances and attract additional sources of support for their work,” said Dr. Graham Hatfull, Chair of the Charles E. Kaufman Foundation’s Scientific Advisory Board, Eberly Family Professor of Biotechnology and Professor of Biological Sciences at the University of Pittsburgh.

Pitt Researchers Receive $2.1 Million to Study Prevention of Deadly Lung Injury

University of Pittsburgh researchers received $2.17 million from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, part of the National Institutes of Health, to study the prevention and early treatment of acute lung injury. Also known as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), acute lung injury is a deadly condition that causes the lung to fail in critically ill patients either directly through injury to the lung, such as pneumonia, or indirectly related to another illness.

University of Pittsburgh researchers received $2.17 million from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, part of the National Institutes of Health, to study the prevention and early treatment of acute lung injury. Also known as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), acute lung injury is a deadly condition that causes the lung to fail in critically ill patients either directly through injury to the lung, such as pneumonia, or indirectly related to another illness.

“Many serious illnesses harm the lung, even when that illness starts elsewhere in the body. A trauma patient may develop ARDS as a result of blood loss or treatments. Severe infection, even outside of the lung, is also a major trigger for ARDS,” said Donald. M. Yealy, MD, professor and chair of Pitt’s Department of Emergency Medicine.

Pitt and UPMC investigators recently published in the New England Journal of Medicine a landmark study that brought new insights into early treatment of sepsis, a deadly form of infection.

Dr. Yealy and co-lead investigator McGowan Institute for Regenerative Medicine affiliated faculty member Derek C. Angus, MD, MPH, Distinguished Professor and Mitchell P. Fink Chair, Department of Critical Care Medicine at Pitt, are members of the steering committee for the Pennsylvania region of the multi-center Prevention and Early Treatment of Acute Lung injury (PETAL) network. The network, which includes a unique combination of emergency physicians and critical care specialists, will conduct clinical trials to prevent, treat, and improve the outcome of patients with ARDS.

“Once lung injury is embedded, it often causes death or long-term damage. Our goal is to recognize the onset of ARDS and treat it before it can do serious harm to the lung,” Dr. Angus said.

AWARDS AND RECOGNITIONS

Dr. Bryan Brown to Receive the TERMIS-AM 2014 Educational Award

McGowan Institute for Regenerative Medicine faculty member Bryan Brown, PhD, will receive the TERMIS-AM 2014 Educational Award during the December 2014 TERMIS-AM Conference in Washington, DC. The Educational Award is presented based on the educational accomplishments of an individual who serves as an advisor/supervisor of students within the field of tissue engineering and regenerative medicine.

McGowan Institute for Regenerative Medicine faculty member Bryan Brown, PhD, will receive the TERMIS-AM 2014 Educational Award during the December 2014 TERMIS-AM Conference in Washington, DC. The Educational Award is presented based on the educational accomplishments of an individual who serves as an advisor/supervisor of students within the field of tissue engineering and regenerative medicine.

Dr. Brown is a Research Assistant Professor with the Department of Bioengineering at the University of Pittsburgh with a secondary appointment in Pitt’s Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Sciences. He is also the Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health Scholar (NIH K12), Magee Women’s Research Institute at the University of Pittsburgh, and an Adjunct Assistant Professor, Department of Clinical Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine at Cornell University.

Nominations for the Educational Award are made by an individual’s student/mentee. Dr. Brown’s nomination was submitted by his student, Travis Prest. Mr. Prest describes his experience with Dr. Brown as follows:

The experience I have gained from working in Dr. Brown’s lab has been invaluable. He creates an environment that promotes learning and innovation. His daily presence in the lab means that he is always available to answer questions or listen to ideas. He is hands-on when needed, but gives us the independence to try out our own ideas. During the first few weeks, my experience deficit was obvious, but Dr. Brown took the time to instruct me. He regularly meets with his students as a whole, as subgroups, and as individuals in order to listen to our progress, critique our theories, and keep us on track. Because of this supervision, he is able to intervene when things start to go astray. … With his support, I am currently in the Research Master’s track, with a goal of pursuing the PhD in bioengineering. This pursuit has been made possible thanks to the guidance of Dr. Brown. Through his leadership and mentoring, I have developed a sense of duty to myself that calls me to succeed in the classroom, in the laboratory, and in my professional life.

Congratulations, Dr. Brown, on this well-deserved recognition!

Dr. Philip LeDuc Selected a Fellow of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers

Philip LeDuc, PhD, Professor of Mechanical Engineering at Carnegie Mellon University and an affiliated faculty member of McGowan Institute for Regenerative Medicine, has been selected a Fellow of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME).

Philip LeDuc, PhD, Professor of Mechanical Engineering at Carnegie Mellon University and an affiliated faculty member of McGowan Institute for Regenerative Medicine, has been selected a Fellow of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME).

Less than 3 percent of ASME’s members have been awarded the prestigious title of Fellow. ASME Fellows must have 10 or more years of active practice in the field of engineering, as well as 10 years of active corporate membership in ASME. Dr. LeDuc was nominated by other ASME members and Fellows for his excellence in research, education, and service. His fellowship was awarded by the ASME Committee of Past Presidents.

Dr. LeDuc also is a Fellow of the Biomedical Engineering Society (BMS) and the American Institute of Medical and Biological Engineering (AIMBE). He also has received many other prestigious awards, including the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation Award and a Beckman Young Investigator Award.

Dr. LeDuc’s research focuses on the possibilities of merging mechanical engineering and biology. He attempts to look at biological processes through a mechanical lens, thereby changing the way we tackle biological issues such as nutrition, bioenergy, and disease.

“The same way Ford would take his pieces and put together the Model T, I’m interested in how I can take pieces and put together an artificial cell that actually has functional behaviors,” Dr. LeDuc said.

Dr. LeDuc founded and directs the Carnegie Mellon Center for the Mechanics and Engineering of Cellular Systems (CMECS), which brings together educators and researchers from across the scientific disciplines to focus their expertise on the questions of cellular mechanics.

Dr. Krzysztof Matyjaszewski Receives 2014 NIMS Award

The National Institute for Materials Science (NIMS) annually hosts the “NIMS Conference” and every year invites the world’s leading researchers to discuss various issues and present their latest results in the fields of materials science, nanotechnology, environment, and energy. NIMS Conference 2014, which is the 11th such conference, was held from July 1 to 3, 2014, at the Tsukuba International Congress Center, under the theme of “Soft Materials Will Open the Way to the Society of the Future.”

The National Institute for Materials Science (NIMS) annually hosts the “NIMS Conference” and every year invites the world’s leading researchers to discuss various issues and present their latest results in the fields of materials science, nanotechnology, environment, and energy. NIMS Conference 2014, which is the 11th such conference, was held from July 1 to 3, 2014, at the Tsukuba International Congress Center, under the theme of “Soft Materials Will Open the Way to the Society of the Future.”

At this conference, the NIMS Award was presented to those researchers who have achieved substantial progress in the field of materials science and technology. Sixty-eight candidates had been nominated from among the world’s top researchers in light of the theme of “soft materials.” A committee of impartial experts made the final choice and selected Mitsuo Sawamoto, PhD, at Kyoto University for his great contribution to the establishment of a precision polymerization method and a precision synthesis method of functional polymers, and Krzysztof Matyjaszewski, PhD, the J.C. Warner Professor of Natural Sciences at Carnegie Mellon University and an affiliated faculty member of the McGowan Institute for Regenerative Medicine, for his success in the development of atom transfer radical polymerization. The award winners gave lectures after the presentation ceremony at the conference.

Regenerative Medicine Podcast Update

The Regenerative Medicine Podcasts remain a popular web destination. Informative and entertaining, these are the most recent interviews:

The Regenerative Medicine Podcasts remain a popular web destination. Informative and entertaining, these are the most recent interviews:

#138 – Dr. Julie Phillippi is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, School of Medicine, with a secondary appointment in the Department of Bioengineering, Swanson School of Engineering. Dr. Phillippi discusses her research in aortic disease.

Visit www.regenerativemedicinetoday.com to keep abreast of the new interviews.

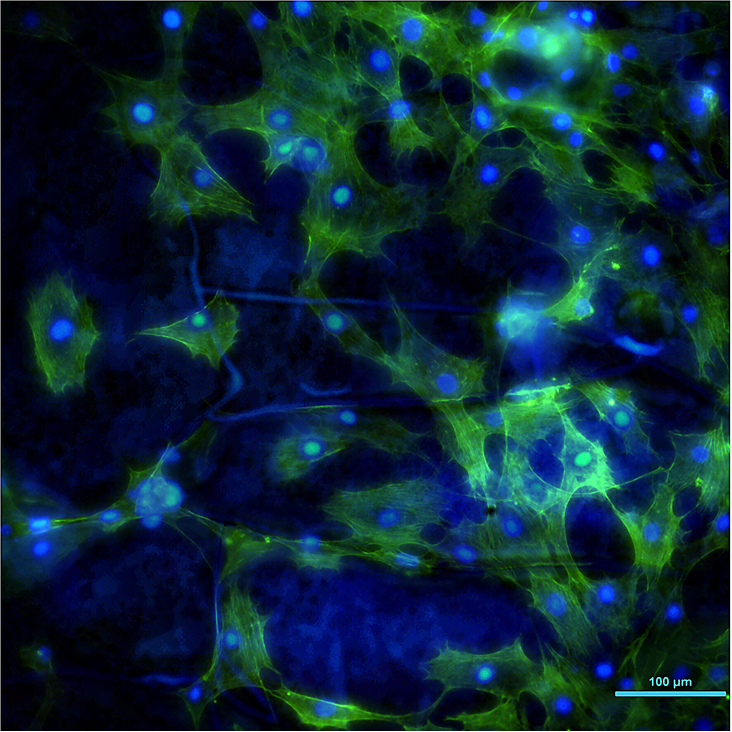

Picture of the Month

These are cells on a Mg disk coated with a selfassembled organosilane film which is only 1 um thick. The blue lines on the background are the cracks in the film. Typically Mg will violently react with water creating H2 bubbles and cells will die on the disks. By coating we were able to slow down the corrosion so cells can colonize the surface. Blue is DAPI (DNA), green is actin.

Photo by Elia Beniash, PhD.