June 2019 | VOL. 18, NO. 06| www.McGowan.pitt.edu

Preventive Drug Therapy May Increase Right-Sided Heart Failure Risk in Patients Who Receive Heart Devices

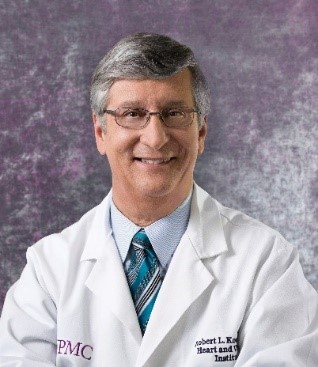

Patients with left-sided heart failure who get implanted devices to improve the pumping of their hearts may be more likely to develop heart failure on the opposite side of their hearts if they are pre-treated with off-label selective vasodilator drugs, according to new research published in Circulation: Heart Failure, an American Heart Association journal. McGowan Institute for Regenerative Medicine Deputy Director Robert Kormos, MD, FAHA, Professor of Cardiothoracic Surgery and Bioengineering at the University of Pittsburgh, past director of UPMC’s Artificial Heart Program, and the Brack G. Hattler Chair of Cardiothoracic Transplantation, is a co-author on this study.

Between 10% and 40% of patients who undergo left-ventricular assist device (LVAD) implantation for left-sided heart failure develop right-sided heart failure — a complication that spells worse outcomes. To head off the complication, physicians sometimes prescribe preemptive treatment with off-label selective vasodilator drugs called phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors (PDE5i). PDE5i drugs are currently approved for use to avoid right heart failure in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension due to causes other than heart disease, which is a different patient group from the ones followed in this study.

PDE5i drugs dilate the pulmonary artery — the large vessel that carries blood away from the heart’s right side and into the lungs. A handful of small studies have shown a possible benefit to this off-label approach in some patients but affirmative data from large-scale studies have been lacking and the current study hopes to help close this gap.

An LVAD is a mechanical heart pump. It’s placed inside a person’s chest, where it helps the heart pump oxygen-rich blood throughout the body. Unlike an artificial heart transplant, LVADs do not replace the heart. LVADs help the heart do its job.

The findings of the new study — the largest analysis to date to assess the utility of this approach — call the preemptive treatment with PDE5i drugs into question.

“We found no benefit of this therapy in patients receiving LVAD devices, including patients with pulmonary vascular disease or right ventricular dysfunction — the very patients who might be expected to benefit most,” said study senior investigator Michael Kiernan, MD, MS, a cardiologist at Tufts Medical Center and assistant professor of medicine at Tufts University School of Medicine in Boston. “Our findings should give pause to clinicians considering this therapy, and we would caution against routine use of these therapies prior to LVAD surgery.”

The results are based on analysis of 11,544 U.S. LVAD recipients who underwent implantation between 2012 and 2017. Of all device recipients, 1,199 (10%) received pre-implantation treatment with PDE5i drugs which target the pulmonary artery to reduce the pressure in the heart’s right ventricle. Overall, 24% of all patients who got LVAD implants developed right-sided heart failure, but the group that got pre-implantation drugs did so at higher rates. To minimize the possible effects of other factors that could bias the outcomes, the researchers matched 1,177patients treated with PDE5i drugs to a group of 1,177 patients who did not receive such preventive therapy but were otherwise similar to the pre-treated group in terms of disease severity, age and the presence of other diseases that could affect outcome and health status.

Compared with those who did not get drug therapy, the group that received vasodilator drugs before LVAD implantation were 31% more likely to develop right-sided heart failure (29% for those treated, compared with 24% among those who did not receive pre-treatment). Additionally, the relative risk of bleeding within a week of LVAD surgery was 46% higher in patients receiving PDE5i therapy (12% of patients receiving therapy versus 8% of those not receiving this therapy), the analysis showed.

RESOURCES AT THE MCGOWAN INSTITUTE

July Histology Special

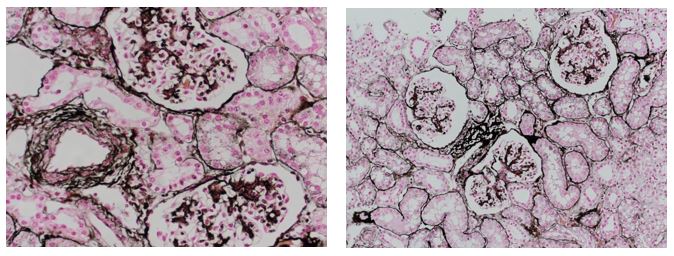

Reticular fibers, or reticulin is a type of fiber in connective tissue, composed of type III collagen secreted by reticular cells. Reticular fibers crosslink to form a fine meshwork (reticulin). This network acts as a supporting mesh in soft tissues such as liver, bone marrow, and the tissues and organs of the lymphatic system.

Jones Silver Stain demonstrates basement membrane and reticulin.

You’ll receive 25% off Jones Silver Stain in July when you mention this ad. Contact Lori at the McGowan Core Histology Lab and ask about our specials. Email perezl@upmc.edu or hartj5@upmc.edu or call 412-624-5265.

As always, you will receive the highest quality histology work with the quickest turn-around time.

Did you know the more samples you submit to the histology lab the less you pay per sample? Contact Lori to find out how!

SCIENTIFIC ADVANCES

In-Utero Surgery in Pittsburgh Region to Treat Spina Bifida

A team of specialists at UPMC Magee-Womens Hospital and UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh have performed UPMC’s first in-utero surgery to close an open neural tube defect in a baby months before her birth. McGowan Institute for Regenerative Medicine affiliated faculty member Stephen Emery, MD, Associate Professor, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, & Reproductive Sciences, Maternal Fetal Medicine, and the Director of the Center for Innovative Fetal Intervention at Magee-Womens Hospital of UPMC, was a member of the surgical team.

When Allee Mullen was pregnant, her baby was diagnosed with spina bifida, a birth defect in which the baby is born with the spinal cord exposed to the air because the overlying bone, muscle and skin do not form properly during development, causing moderate-to-severe physical disabilities. There are several types of spina bifida, and Mullen’s baby was diagnosed with a myelomeningocele, the most serious form of spina bifida.

Spina bifida affects about 1,500 babies born each year in the United States. At UPMC Children’s Hospital, physicians close defects like this one in 10 to 20 infants each year following delivery.

This new procedure has been performed at several centers across the United States but has not been available in this area. In January 2019, an interdisciplinary team of maternal-fetal medicine, obstetric anesthesiology, neonatology and pediatric neurosurgery specialists from both UPMC Magee and UPMC Children’s performed and assisted during the complex surgery on Mullen and her unborn baby, who was at 25 weeks gestation at the time.

“This surgery is risky, but research shows that babies who are closed in-utero have better neurologic outcomes than babies treated after birth,” said Dr. Emery.

A randomized controlled trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine showed that, compared to surgery after birth, fetal surgery resulted in improved leg function and halved the risk for hydrocephalus—fluid buildup in the brain—a common complication of spina bifida.

“Being able to perform this surgery in-utero offers many benefits to the baby, but one of the most important is improving the chances a child will be able to walk on their own,” said Stephanie Greene, MD, director of Vascular and Perinatal Neurosurgery, UPMC Children’s Hospital.

Two months following the prenatal surgery, Mullen’s baby girl, Emery Greene Mullen, named after the lead surgeons, was born.

“Our initial tests show that Emery has almost entirely normal leg function. It can take up to a year to rule out hydrocephalus, but we are very hopeful. The neurologic outcome is definitely better than if her surgery had been done after birth,” added Dr. Greene, associate professor of Neurological Surgery, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine.

“Pregnant women diagnosed with fetal spina bifida might very well be candidates for the in-utero procedure,” added Dr. Emery. “We are excited and proud to now offer this service at UPMC Magee to patients living in the western Pennsylvania and tri-state regions.”

“To be the first patient in Pittsburgh, I hope mothers will learn about my story and the hope for Emery’s future, and if they are in the same position as me, they will know there is an option and it is close to home,” said Allee Mullen. “I thank Dr. Emery, Dr. Greene and the entire team for what they did for Emery and our family.”

Illustration: Dr. Stephen Emery, Allee and Emery Greene Mullen, and Dr. Stephanie Greene. UPMC.

Challenges of Pancreatic Cancer and Treatment Advances

With Alex Trebek’s recent announcement that his pancreatic cancer is in remission, many people have wondered if this difficult cancer is now easier to treat. Pancreatic cancer remains a major cancer killer, but advances are happening.

As a medical oncologist who specializes in treating and studying pancreatic cancer, in his article for The Conversation, McGowan Institute for Regenerative Medicine affiliated faculty member Nathan Bahary, MD, PhD, Associate Professor in the Department of Medicine, Division of Oncology at the University of Pittsburgh with a secondary appointment as an Associate Professor in Microbiology and Molecular Genetics, provides insights, including some from the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) meeting previously held this year.

Pancreatic cancer and its toll

We oncologists, or cancer specialists, call the disease “pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma,” or PDAC. It is a leading cause of cancer-related death, currently ranking as the seventh leading cause of cancer deaths globally and the third in the U.S.

Often diagnosed at an advanced stage, pancreatic cancer has a low survival rate of 9% or less.

Although cancers are usually classified as stages from I to IV, in PDAC we have found that a different system which corresponds to how we actually treat these tumors is more useful. The earliest stage is when the cancer is determined to be surgically resectable, that is, removable through surgery. About 15% of patients’ tumors are found at this stage.

About 40% of patients’ tumors have further progressed to where they attach themselves to or encompass local structures. This is further broken down into borderline tumors that, although technically removable, require chemotherapy and radiation therapy prior to surgery to ensure their complete removal.

Locally advanced tumors cannot be surgically removed in most cases as they completely surround critical blood vessels or infiltrate into adjoining critical organs.

The remainder of pancreatic cancers are already metastatic – they have already spread to distant areas. Nearly all long-term pancreatic cancer survivors are diagnosed when their cancer is, or can be made, surgically removable. Contrarily, because of the limited number of treatment options, and inherent resistance to treatment, exceedingly few five-year survivors present with Stage IV disease.

Lack of screening an impediment

A key challenge in treating pancreatic cancer is the lack of good screening techniques to identify such cancers in their earliest stages, as the pancreas lies in an anatomically unfavorable position for early diagnosis, toward the back of the abdomen.

By the time the diagnosis of pancreatic adenocarcinoma is suspected, typically by symptoms such as jaundice, pain and weight loss, the tumor has already grown to a point where surgical removal is difficult. Critical vascular and other structures hamper surgical excision. Or, it has grown to a point where it has spread to distant sites.

Additionally, well before a physician diagnoses a patient’s pancreatic cancer, there is often what we call microscopic metastatic disease. This means that cancer cells are already hiding in other parts of the body. Preoperative and postoperative chemotherapy and radiation are used to try to kill such stealth tumor cells. However, despite these treatments, most patients whose tumors are surgically removed will die of recurrence resulting from these remaining tumor cells.

Chemo, and more chemo

Once spread to other organs either at presentation or in relapse, PDAC is not curable except in rare circumstances. However, treatment of patients with metastatic disease can yield benefits in terms of overall survival and a quality of life.

Historically, standard chemotherapy for these patients has included one or two drugs, but newer chemotherapy combinations are being used in patients who can tolerate more aggressive systemic therapy. Some of these may be used in combination.

In particularly fit patients, another sequence of chemotherapy after the first drugs yields continued responses, but unfortunately, rarely leads to a complete remission of all disease.

Up to two-thirds of patients will gain benefit from these sequential chemotherapy treatments, resulting in the halt of their disease growth, or have a partial decrease in the amount of their tumor. In the past, the one-year survival of patients with metastatic disease was 15-20%. New combinations given sequentially can raise the one-year survival rate to about 50%.

Inevitably, due to the development of resistance in a patient’s tumor to chemotherapy, as well as toxicities of treatment, even those who initially respond succumb to disease progression. By five years after diagnosis, patient survival with metastatic disease is less than 3%.

Also, PDAC is mostly diagnosed in older individuals with concomitant medical issues, and this limits treatment. Chemotherapy tolerance and survival is poorer in many individuals, although treatment can still yield benefits in terms of quality of life.

Hope on the horizon?

Recent advances in our molecular understanding of PDAC have yielded new treatment paradigms with the hope of improving these results. We know that some people with pancreatic cysts, or pockets of fluid within the pancreas, are at increased risk of developing pancreatic cancer. Yet distinguishing potentially cancerous cysts from benign, or non-cancerous, ones has been difficult. Recent molecular techniques have been developed to help stratify the risks of developing cancer in these cysts, enabling their surgical removal during their earliest and most curable stage.

Similarly, recent research has yielded a better understanding of the molecular changes that can lead to the development of pancreatic cancer. Studies have demonstrated that up to 10% of pancreatic cancer patients have DNA alterations that can be identified in their blood, that are potentially clinically useful, and that may also raise the risk to family members who have those same DNA changes for developing PDAC. Clinical treatment strategies are being developed to not only direct treatment at these specific changes, but also to develop screening techniques to identify PDAC in similarly affected family members at an earlier and more treatable stage.

For example, patients who harbor a germline change in the BRCA2 gene are at higher risk of developing pancreatic cancer as well as breast, ovarian, prostate and other cancers. A class of drugs called PARP inhibitors, which have been utilized in treating breast and ovarian cancers that are dependent on BRCA2, have been recently shown to offer a survival benefit in pancreatic patients whose tumors harbor the same BRCA2 gene mutations.

Evaluation of pancreatic cancer DNA has yielded insights into a number of altered genes that are yielding better and more directed therapies. For example, researchers have found targetable alterations in the ALK and NTRK genes in tumors of particular pancreatic cancer patients. Identification of these altered genes in patient’s tumors allows for much better tolerated and effective treatments directed at these tumor-causing genes. As a result, it is now considered standard of care to offer germline and tissue DNA analysis to all pancreatic cancer patients to identify such actionable gene defects.

Immunotherapy, which has been transforming treatment in a host of other cancers, may one day be effective. Although no large randomized trial has yet proven the efficacy of immune therapies in pancreatic cancer, data published in April 2019 utilizing a combination of drugs have yielded hopeful preliminary results.

Other clinical studies targeting the unique metabolism of pancreatic cancers or the surrounding tissue are underway as well. Clearly, given the otherwise poor survival statistics for pancreatic cancer using our classical therapy options, the future of pancreatic cancer treatment lies in the development of novel agents to supplant or be added to current chemotherapy regimens.

Rapid Fluid Removal Increases Death Risk in Kidney Patients

The faster fluid is removed using continuous dialysis from patients with failing kidneys, the higher the likelihood they will die in the next several months, according to a study published today in JAMA Network Open by University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine researchers. McGowan Institute for Regenerative Medicine affiliated faculty members Gilles Clermont, MD, and John Kellum, MD, are co-authors of the study.

Nearly two-thirds of critically ill patients with acute kidney injury have extra fluid accumulating in their bodies, which can put pressure on their lungs and cause injury to other organs. To relieve that pressure, clinicians routinely remove the excess fluid from the blood while performing dialysis in the intensive care unit. But there is no guidance on how fast that fluid should be removed.

“We want to get this excess fluid out of our patients before it causes damage but, in removing it, we’re actually causing a controlled loss of fluid that can sometimes cause stress on the heart and lead to dangerously low blood pressure,” said lead author Raghavan Murugan, MD, MS, associate professor in Pitt’s Department of Critical Care Medicine and UPMC physician. “So the question—how rapidly to remove fluid—has been asked in the critical care community for many years, but there’s been no good answer.”

Previous studies in outpatients who are not critically ill found that routine dialysis—a procedure to remove waste, toxins, salt and extra water from the blood of people whose kidneys have failed—when performed too quickly, is associated with increased risk of death.

Dr. Murugan partnered with senior author Rinaldo Bellomo, MD, PhD, a professor of intensive care medicine at the University of Melbourne in Australia to find out if that finding extends to critically ill patients. Their team examined data from 1,434 patients that Dr. Bellomo had previously collected for the Randomized Evaluation of Normal vs. Augmented Level of Renal Replacement Therapy trial, which was conducted between December 30, 2005 and November 28, 2008 in 35 intensive care units in Australia and New Zealand.

The research team found that for every 0.5 milliliter increase in fluid removed per kilogram of the patient’s weight per hour (0.5 mL/kg/hr), their risk of death increases. That translates to a 51% to 66% higher risk of death in the next three months for critically ill patients for whom excess fluid is removed at a rate greater than 1.75 mL/kg/hr, compared to patients for whom excess fluid is removed at a rate less than 1.01 mL/kg/hr.

For the average older American male, that’s a difference of removing a gallon of fluid in about one day versus a little under two days.

Dr. Murugan is quick to point out that his analysis shows association, not causation; until a clinical trial is performed to specifically test the effects of removing fluid faster versus slower, he cannot say for sure that removing fluid slowly is better for the patient. And, in some cases, such as imminent heart failure, Dr. Murugan says a more rapid removal of fluid might be warranted to prevent sudden death.

“You have to balance the pros and the cons and decide how fast to remove fluid based on your patient’s clinical condition,” said Dr. Murugan, who also is a member of Pitt’s Clinical Research, Investigation, and Systems Modeling of Acute Illness Center and the Center for Critical Care Nephrology. “But in a patient where I can’t find an immediate need to get fluid out quickly, I’ll be removing fluid at a slower rate until we get definitive results and guidance from a clinical trial.”

Drs. Peter Rubin and Albert Donnenberg Bring Adipose Cell Therapy to Italy

Patients at UPMC Salvator Mundi International Hospital in Italy will soon have increased access to innovative methods of tissue regeneration that could improve healing and outcomes with reconstructive or aesthetic plastic surgery.

McGowan Institute for Regenerative Medicine affiliated faculty members J. Peter Rubin, MD, FACS, chair of the UPMC Department of Plastic Surgery, and Albert Donnenberg, PhD, director of the UPMC and UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh Hematopoietic Stem Cell Laboratories, are collaborating with colleagues at UPMC Salvator Mundi in Rome to develop a dedicated clinical program focused on adipose-derived regenerative therapies. The therapies are used for breast reconstruction, as well as treating radiation fibrosis from cancer therapy, degenerative joint disease, tendon injuries and burn wounds, among other conditions.

“Adipose tissue, or fat, is taken from the patient’s abdominal area by minimally invasive methods, and then processed in different ways to take advantage of the regenerative effects and the ability to restore volume in the soft tissues,” said Dr. Rubin, who is also co-director of the University of Pittsburgh Adipose Stem Cell Center. “We have been researching the biology of adipose tissue and adipose stem cells for regenerative therapies at Pitt and UPMC since 2002, and we are excited to share our knowledge and clinical practices with our colleagues in Italy.”

UPMC Salvator Mundi’s team of physicians will be establishing a center of excellence in regenerative surgery. Together with Drs. Rubin and Donnenberg, they will work to achieve the highest standards for adipose cell therapy in Italy, including future certification from an international accrediting body—similar to how UPMC is certified in Pittsburgh.

“The arrival of this new method of adipose cell therapy in Italy is a prime example of the benefits that come with the partnership between UPMC Salvator Mundi and the world-renowned experts in plastic surgery and regenerative medicine at UPMC and the University of Pittsburgh,” said Lucio Cappelli, MD, a physician who is leading this effort in Rome, along with Carlo Macro, MD, and Simone Moroni, MD. “This collaborative effort to share research is improving care for patients globally, bringing the best possible treatments close to home.”

Plastic and reconstructive surgery physicians from Sapienza University in Rome, one of the most prestigious universities in Europe, will also take part in the clinical and scientific collaboration, and Dr. Rubin will become a visiting professor there.

Pitt and CMU Researchers Discover How the Brain Changes When Mastering a New Skill

Mastering a new skill – whether a sport, an instrument, or a craft – takes time and training. While it is understood that a healthy brain is capable of learning these new skills, how the brain changes in order to develop new behaviors is a relative mystery. More precise knowledge of this underlying neural circuitry may eventually improve the quality of life for individuals who have suffered brain injury by enabling them to more easily relearn everyday tasks.

Researchers from the University of Pittsburgh and Carnegie Mellon University (CMU) recently published an article in PNAS that reveals what happens in the brain as learners progress from novice to expert. They discovered that new neural activity patterns emerge with long-term learning and established a causal link between these patterns and new behavioral abilities. McGowan Institute for Regenerative Medicine affiliated faculty member Elizabeth Tyler-Kabara, MD, PhD, Associate Professor in the Departments of Neurological Surgery, Bioengineering, and Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation at the University of Pittsburgh, the Director of the Spasticity and Movement Disorder Program at Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC, Medical Staff of Children’s Hospital and of UPMC Presbyterian and Shadyside Hospitals, and Consultant Staff of Magee Womens Hospital of UPMC, is a co-author of the study.

The research was performed as part of the Center for the Neural Basis of Cognition, a cross-institutional research and education program that leverages the strengths of Pitt in basic and clinical neuroscience and bioengineering with those of CMU in cognitive and computational neuroscience.

The project was jointly mentored by Aaron Batista, PhD, associate professor of bioengineering at Pitt’s Swanson School of Engineering; Byron Yu, PhD, associate professor of electrical and computer engineering and biomedical engineering at CMU; and Steven Chase, PhD, associate professor of biomedical engineering and the Neuroscience Institute at CMU. The work was led by Pitt bioengineering postdoctoral associate Emily Oby, PhD.

“We used a brain-computer interface (BCI), which creates a direct connection between our subject’s neural activity and the movement of a computer cursor,” said Dr. Oby. “We recorded the activity of around 90 neural units in the arm region of the primary motor cortex of Rhesus monkeys as they performed a task that required them to move the cursor to align with targets on the monitor.”

To determine whether the monkeys would form new neural patterns as they learned, the research group encouraged the animals to attempt a new BCI skill and then compared those recordings to the pre-existing neural patterns.

“We first presented the monkey with what we call an ‘intuitive mapping’ from their neural activity to the cursor that worked with how their neurons naturally fire and which didn’t require any learning,” said Dr. Oby. “We then induced learning by introducing a skill in the form of a novel mapping that required the subject to learn what neural patterns they need to produce in order to move the cursor.”

Like learning most skills, the group’s BCI task took several sessions of practice and a bit of coaching along the way.

“We discovered that after a week, our subject was able to learn how to control the cursor,” said Dr. Batista. “This is striking because by construction, we knew from the outset that they did not have the neural activity patterns required to perform this skill. Sure enough, when we looked at the neural activity again after learning we saw that new patterns of neural activity had appeared, and these new patterns are what enabled the monkey to perform the task.”

These findings suggest that the process for humans to master a new skill might also involve the generation of new neural activity patterns.

“Though we are looking at this one specific task in animal subjects, we believe that this is perhaps how the brain learns many new things,” said Dr. Yu. “Consider learning the finger dexterity required to play a complex piece on the piano. Prior to practice, your brain might not yet be capable of generating the appropriate activity patterns to produce the desired finger movements.”

“We think that extended practice builds new synaptic connectivity that leads directly to the development of new patterns of activity that enable new abilities,” said Dr. Chase. “We think this work applies to anybody who wants to learn – whether it be a paralyzed individual learning to use a brain-computer interface or a stroke survivor who wants to regain normal motor function. If we can look directly at the brain during motor learning, we believe we can design neurofeedback strategies that facilitate the process that leads to the formation of new neural activity patterns.”

Sedation, Paralysis Do Not Improve Survival of ICU Patients

Reversibly paralyzing and heavily sedating hospitalized patients with severe breathing problems do not improve outcomes in most cases, according to a National Institutes of Health-funded clinical trial conducted at dozens of North American hospitals and led by clinician-scientists at the University of Pittsburgh and University of Colorado schools of medicine.

The trial—which was stopped early due to futility—settles a long-standing debate in the critical care medicine community about whether it is better to paralyze and sedate patients in acute respiratory distress to aid mechanical ventilation or avoid heavy sedation to improve recovery. The results, presented at the American Thoracic Society’s Annual Meeting, also is published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“It’s been a conundrum—on the one hand, really well-done studies have shown that temporarily paralyzing the patient to improve mechanical breathing saves lives. But you can’t paralyze without heavy sedation, and studies also show heavy sedation results in worse recovery. You can’t have both—so what’s a clinician to do?” said senior author Derek Angus, MD, MPH, who holds the Mitchell P. Fink Endowed Chair of the Pitt School of Medicine’s Department of Critical Care Medicine and is an affiliated faculty member of the McGowan Institute for Regenerative Medicine. “Our trial finally settles it—light sedation with intermittent, short-term paralysis if necessary is as good as deep sedation with continuous paralysis.”

The Re-evaluation Of Systemic Early neuromuscular blockade (ROSE) trial is the first of the new National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s (NHLBI) Prevention & Early Treatment of Acute Lung Injury (PETAL) Network. PETAL develops and conducts randomized controlled clinical trials to prevent or treat patients who have, or who are at risk for, acute lung injury or acute respiratory distress syndrome. The trial network places particular emphasis on early detection by requiring every network member institute include both critical care and emergency medicine, acute care or trauma principal investigators to ensure that critical health issues are recognized and triaged as fast as possible to improve patients’ odds of recovery before they are even transferred to the intensive care unit.

From January 2016 through April 2018, 1,006 patients at 48 U.S. hospitals were enrolled in ROSE within hours after onset of moderate-to-severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. Half were given a 48-hour continuous neuromuscular blockade—a medication that paralyzes them—along with heavy sedation because it is traumatizing to be paralyzed while conscious. The other half were given light sedation, and the clinician had the option of giving a small dose of neuromuscular blockade that would wear off in under an hour to ease respiratory intubation.

“This is the kind of important question that the PETAL network was designed to answer efficiently,” said James Kiley, PhD, director of the Division of Lung Diseases at the NHLBI. “These results will help practicing clinicians make decisions early on in the care of their patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome.”

The trial was needed because a French trial found in 2010 that neuromuscular blockade reduced mortality. However, in that trial all participants were heavily sedated, regardless of whether they received the neuromuscular blockade or not. In recent years, particularly in North America, clinicians have trended away from heavy sedation, which is associated with cardiovascular complications, delirium and increased difficulty weaning patients from mechanical ventilation.

In the ROSE trial, the patients who received the neuromuscular blockade and sedation developed more cardiovascular issues while in the hospital, but there were no significant differences in mortality between the two groups three, six or 12 months later, said David Huang, MD, MPH, who oversaw clinical implementation of the trial and is an associate professor of critical care and emergency medicine at Pitt’s School of Medicine.

“Due to the exceptional work of our research coordinators, the study completed enrollment ahead of schedule, a rarity in multicenter clinical trials,” said lead author Marc Moss, MD, The Roger S. Mitchell Professor of Medicine and head of the Division of Pulmonary Sciences and Critical Care Medicine at the University of Colorado’s Department of Medicine. “Therefore, these important findings are available to health care providers sooner and should result in more rapid implementation of enhanced care for our patients.”

Dr. Angus, who also directs Pitt’s Clinical Research, Investigation, and Systems Modeling of Acute Illness (CRISMA) Center, said the trial results make him confident when he says that avoiding paralysis and deep sedation is the best practice for most patients hospitalized with breathing problems. However, he notes that future trials will be needed to tease out whether there is a subpopulation of patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome who still benefit from neuromuscular blockade.

Dr. Anne Robertson Delivers Keynote Lecture at International Conference

McGowan Institute for Regenerative Medicine affiliated faculty member Anne Robertson, PhD, William Kepler Whiteford Endowed Professorship of Mechanical Engineering and Materials Science and Professor of Bioengineering, was among a prestigious group of scholars invited to give a keynote lecture at the 6th International Conference on Computational and Mathematical Biomedical Engineering. The conference was hosted by Tohoku University in Sendai City, Japan.

The title of Dr. Robertson’s lecture was “Identifying Physical Causes of Failure in Brain Aneurysms.” A subarachnoid hemorrhage, a type of stroke with high mortality and disability rates, is often caused by the rupture of a cerebral aneurysm. However, if the aneurysm is not ruptured, treatment for this condition can be more dangerous than the risk of rupture itself. Therefore, there is a need to develop reliable methods for assessing rupture risk.

Dr. Robertson’s presentation discussed her group’s recent findings which demonstrate the need to identify the actual physical causes for wall vulnerability as a vital component of accessing rupture risk. This research is done by using data driven computational simulations obtained from human aneurysm tissue. New tools for mapping heterogeneous experimental data for the wall to the 3D reconstructed vascular model make it possible to evaluate the associations between critical aspects of aneurysm wall structure and both hemodynamic and intramural stress.

Other Pitt members of this multi-institutional research team include Spandan Maiti, PhD, who holds a primary appointment in Bioengineering and a secondary appointment in MEMS and McGowan Institute affiliated faculty member Simon Watkins, PhD, Distinguished Professor of the Department of Cell Biology and Director of the Center for Biologic Imaging. Doctoral students Fangzhou Cheng, Michael Durka, Ronald Fortunato, Piyusha Gade and Chao Sang as well as postdoctoral researchers Yasutaka Tobe, PhD, and Eliisa Ollikainen, PhD, also made substantial contributions to this work.

One of the main focuses of Dr. Robertson’s research is the relationship between soft tissue structure and mechanical function in health and disease for soft tissues such as cerebral arteries, cerebral aneurysms, tissue engineered blood vessels and the bladder wall. Her research is heavily supported by the National Institutes of Health where she is a standing member of the Neuroscience and Ophthalmic Imaging Technologies (NOIT) Study Section.

Scientists Remind Immune Cells Whose Side They Should Be On

An international group of scientists in the joint study of the laboratory of the Wistar Institute, University of Pittsburgh, and I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University discovered the change in activity of one of the immune cells types called neutrophils during cancer development: They begin to prevent other immune cells from fighting tumors, and thus decelerate treatment. The scientists found protein causing such changes and demonstrated that suppressing its activity in the cells delays cancer development. The research details are published in Nature. McGowan Institute for Regenerative Medicine affiliated faculty member Valerian Kagan, PhD, Professor and Vice-Chairman in the Department of Environmental and Occupational Health as well as a Professor in the Department of Pharmacology and Chemical Biology, the Department of Radiation Oncology, and the Department of Chemistry at the University of Pittsburgh, and also the Director of the Center for Free Radical and Antioxidant Health, is a co-author of the study.

The study is focused on myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) developing from neutrophils. In some cases (e.g. in cancer, during inflammation or autoimmune diseases), these immune cells start to fight against other immune cells instead of bacteria and fungi. Thus, they weaken the body reaction against the tumor and decrease cancer treatment efficiency.

Despite the fact that the activity of MDSCs complicates the treatment, the mechanisms responsible for its change are still poorly studied. Earlier research showed that, during oncological disease, polyunsaturated fats (lipids) accumulate in some types of immune cells, so the scientists decided to check whether the dysfunction of lipid metabolism in neutrophils is linked to changes in their activity. They compared the fat content in the cells of healthy mice and animals with different types of cancer, and the latter group had much higher amounts of fat.

After that, scientists led by professor Dmitry Gabrilovich, MD, PhD, at the Wistar Institute looked at the difference between the activity (expression) of genes in suppressor cells in healthy and sick mice. They were especially interested in genes that encode proteins carrying fatty acids through the cell wall. A great difference was observed in the activity of the Slc27a2 gene encoding one of these proteins, FATP2; the activity of other genes did not differ. Increased FATP2 content in cancer was present in people as well, and these were patients with different types of cancer.

Then the researchers checked whether FATP2 is able to somehow affect the activity of neutrophils. They compared the rate of tumor growth in mice with “deactivated” and activated Slc27a2 and found that in the former group the disease developed more slowly. The scientists also checked whether the efficiency of such therapy depends on other diseases. Experiments showed that if the animal has immunity dysfunction, the treatment gave much smaller results. Besides, the combination of this type of therapy with the suppression of the production of immune checkpoints—molecules that weaken the immune response—showed good efficiency. The activity of checkpoints is useful during autoimmune diseases, but undesirable in cancer.

“One of the contemporary trends in anticancer therapy is immune therapy. This is a type of treatment when pharmaceuticals do not kill tumor cells directly but instead stimulate the body’s natural defenses to fight the cancer. Among treatments of this kind, elimination of the modified immune cells in the tumor microenvironment that are reprogrammed to suppress the normal immune surveillance is a very promising approach. Our study published in Nature describes research of this type that attempts to encourage neutrophils to “recall their important immune functions.” Based on the conducted research and deciphered mechanisms, the successful treatment has been proposed and achieved using experimental models of tumor-bearing animals,” added Dr. Kagan.

Sanjeev G. Shroff, PhD Joins the McGowan Institute Executive Committee

Sanjeev G. Shroff, PhD Distinguished Professor and Gerald E. McGinnis Chair in Bioengineering, and Professor of Medicine, and Chair of the Department of Bioengineering at the University of Pittsburgh has joined the McGowan Institute for Regenerative Medicine Executive Committee. Dr. Shroff is widely recognized as a distinguished scholar in the cardiovascular arena, as a mentor, and as a leader of the Department of Bioengineering.

The Committee provides guidance to the Institute on strategic issues and opportunities. The Committee also reviews and approves all secondary faculty appointments in the Institute.

The other members of the Executive Committee are:

Summer “Happenings”: Regenerative Medicine Summer School and 8-Week Internships

The 6th Annual McGowan Institute Regenerative Medicine Summer School (June 16-21, 2019) has just concluded with 19 students from universities across the U.S. being introduced to the science, as well as the clinical and commercial potential of regenerative medicine-based therapies through a combination of lectures and hands-on laboratory activities.

The summer program is under the direction of Bryan N. Brown, PhD, Associate Professor, Department of Bioengineering, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Sciences, and the Clinical and Translational Science Institute. Dr. Brown is also the Director of Educational Outreach-McGowan Institute.

Following the summer school week, ten of the trainees began an 8-week internship where each student is working in the lab of a McGowan affiliated faculty member.

Through the generosity of the Bayer USA Foundation, this year’s program is being offered to the participating students at no cost to the participants. The summer school program has been endorsed by the Society for Biomaterials and the Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine International Society (TERMIS).

Our thanks to the faculty and staff for your contributions to this very successful event.

AWARDS AND RECOGNITION

Dr. Timothy Billiar Receives Honor from the Elmezzi Graduate School of Molecular Medicine

The Elmezzi Graduate School of Molecular Medicine is part of Northwell Health and functions in partnership with The Feinstein Institute for Medical Research. The Elmezzi Graduate School of Molecular Medicine was established in 1994 and is a PhD program for physicians who wish to pursue careers in biomedical research. The program is an individually tailored program with a strong emphasis on translational research.

Along with celebrating and recognizing this year’s graduates, honorary degrees – Candidate for Degree of Doctor of Science honoris causa – were given to two researchers who advanced biomedical research and improved medical treatment for patients. One of the recipients this year for this prestigious honor is McGowan Institute for Regenerative Medicine faculty member Timothy Billiar, MD, the George Vance Foster endowed professor and chair in the Department of Surgery and a deputy director in the Molecular Medicine Institute.

Dr. Billiar’s current areas of research include:

- Nitric oxide and hepatic function in sepsis and trauma

- Post-traumatic sepsis: regulation of LPS binding protein

- Training in trauma and sepsis research

- Molecular biology of hemorrhagic shock

As a result of his research, Dr. Billiar has gained an international reputation for his contributions to understanding the role of nitric oxide in gene therapy, trauma, liver disease, and other potential clinical applications. He holds six US patents associated with his research.

Congratulations, Dr. Billiar!

Critical Care Medicine Professor Michael Pinsky, MD, Becomes Society Fellow

McGowan Institute for Regenerative Medicine affiliated faculty member Michael Pinsky, MD, Professor of Critical Care Medicine (primary), Bioengineering, Cardiovascular Diseases, Clinical & Translational Science, and Anesthesiology at the University of Pittsburgh, has been elevated to the rank of APS Fellow by the American Physiological Society.

The fellowship is an honor bestowed on senior scientists who have “demonstrated excellence in science, have made significant contributions to the physiological sciences and served the society.”

Dr. Pinsky has been a society member since 1984. During his professional career, he has edited 27 medical textbooks, authored over 350 peer-reviewed publications and over 250 chapters and supported over 400 abstract presentations. He is also the editor-in-chief of Medscape’s critical care medicine section.

Congratulations, Dr. Pinsky!

Dr. Tetsuro Sakai to Head Transplant Anesthesia Society

McGowan Institute for Regenerative Medicine affiliated faculty member Tetsuro Sakai, MD, PhD, Professor of Anesthesiology and Professor of the Clinical Translational Science Institute, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, and Director of Scholarly Development in the Department of Anesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine, was selected as president-elect for the Society for the Advancement of Transplant Anesthesia (SATA) for a two-year term (2019-2021).

SATA is a professional association serving the needs of anesthesiologists and critical care specialists involved in the practice of transplantation medicine and surgery.

Congratulations, Dr. Sakai!

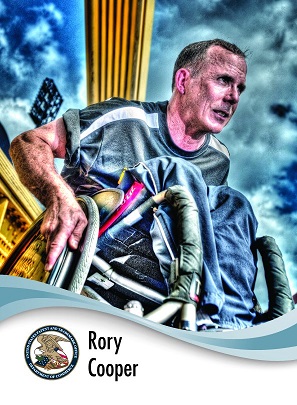

HERL Director Dr. Rory Cooper Joins Hall of Inventors

McGowan Institute for Regenerative Medicine affiliated faculty member Rory Cooper, PhD, director of the Human Engineering Research Laboratories at Pitt, was recently honored with his U.S. Patent and Trademark Office inventor trading card and portrait (pictured).

Dr. Cooper is the 28th inventor and the first Pitt professor to receive this honor, which was established in 2012. Other inventors who have received this honor include Thomas Edison, George Washington Carver, Abraham Lincoln and Hedy Lamarr, among others.

Dr. Cooper has over two dozen patents in his name, with his portrait featuring one of them — the Ergonomic Dual Surface Wheelchair Pushrim, a wheelchair accessory designed to relieve stress on the wheelchair pusher’s upper body. He is also the associate dean for inclusion and the FISA/Paralyzed Veterans of America Distinguished Professor at Pitt’s School of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences.

Congratulations, Dr. Cooper!

Illustration: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (click for view of card front and back: USPTO.)

Nancy Briones Receives Staff Professional Development Award

The 2019 recipient of the Pitt Staff Association Council’s Staff Professional Development Award is Nancy Briones, Financial Analyst at the McGowan Institute. The award which was developed in honor of Ronald W. Frisch, former University of Pittsburgh associate vice chancellor for Human Resources, provides monetary resources to selected University of Pittsburgh staff members to pursue professional enrichment opportunities.

Nancy will use the $500 award to finish her Master of Accountancy degree in December 2020, at Joseph M. Katz Graduate School of Business.

Congratulations Nancy!

Photo L to R: April O’Neil, co-chair of the Staff Council operations committee; Nancy Briones, Darleen Noah, Director of Fiscal Operations, McGowan Institute, and; Andy Stephany, Staff Council President

Regenerative Medicine Podcast Update

The Regenerative Medicine Podcasts remain a popular web destination. Informative and entertaining, these are the most recent interviews:

#198 –– Dr. Buddy Ratner discusses his research in polymeric biomaterials and advancing kidney dialysis. He also discusses his roll in the Journal of Immunology and Regenerative Medicine..

Visit www.regenerativemedicinetoday.com to keep abreast of the new interviews.

PUBLICATION OF THE MONTH

Author: Seymour CW, Kennedy JN, Wang S, Chang CH, Elliott CF, Xu Z, Berry S, Clermont G, Cooper G, Gomez H, Huang DT, Kellum JA, Mi Q, Opal SM, Talisa V4 van der Poll T, Visweswaran S, Vodovotz Y, Weiss JC, Yealy DM, Yende S, Angus DC

Title: Derivation, Validation, and Potential Treatment Implications of Novel Clinical Phenotypes for Sepsis

Summary: IMPORTANCE: Sepsis is a heterogeneous syndrome. Identification of distinct clinical phenotypes may allow more precise therapy and improve care.

OBJECTIVE: To derive sepsis phenotypes from clinical data, determine their reproducibility and correlation with host-response biomarkers and clinical outcomes, and assess the potential causal relationship with results from randomized clinical trials (RCTs).

DESIGN, SETTINGS, AND PARTICIPANTS: Retrospective analysis of data sets using statistical, machine learning, and simulation tools. Phenotypes were derived among 20 189 total patients (16 552 unique patients) who met Sepsis-3 criteria within 6 hours of hospital presentation at 12 Pennsylvania hospitals (2010-2012) using consensus k means clustering applied to 29 variables. Reproducibility and correlation with biological parameters and clinical outcomes were assessed in a second database (2013-2014; n = 43 086 total patients and n = 31 160 unique patients), in a prospective cohort study of sepsis due to pneumonia (n = 583), and in 3 sepsis RCTs (n = 4737).

EXPOSURES: All clinical and laboratory variables in the electronic health record.

MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES: Derived phenotype (α, β, γ, and δ) frequency, host-response biomarkers, 28-day and 365-day mortality, and RCT simulation outputs.

RESULTS: The derivation cohort included 20 189 patients with sepsis (mean age, 64 [SD, 17] years; 10 022 [50%] male; mean maximum 24-hour Sequential Organ Failure Assessment [SOFA] score, 3.9 [SD, 2.4]). The validation cohort included 43 086 patients (mean age, 67 [SD, 17] years; 21 993 [51%] male; mean maximum 24-hour SOFA score, 3.6 [SD, 2.0]). Of the 4 derived phenotypes, the α phenotype was the most common (n = 6625; 33%) and included patients with the lowest administration of a vasopressor; in the β phenotype (n = 5512; 27%), patients were older and had more chronic illness and renal dysfunction; in the γ phenotype (n = 5385; 27%), patients had more inflammation and pulmonary dysfunction; and in the δ phenotype (n = 2667; 13%), patients had more liver dysfunction and septic shock. Phenotype distributions were similar in the validation cohort. There were consistent differences in biomarker patterns by phenotype. In the derivation cohort, cumulative 28-day mortality was 287 deaths of 5691 unique patients (5%) for the α phenotype; 561 of 4420 (13%) for the β phenotype; 1031 of 4318 (24%) for the γ phenotype; and 897 of 2223 (40%) for the δ phenotype. Across all cohorts and trials, 28-day and 365-day mortality were highest among the δ phenotype vs the other 3 phenotypes (P < .001). In simulation models, the proportion of RCTs reporting benefit, harm, or no effect changed considerably (eg, varying the phenotype frequencies within an RCT of early goal-directed therapy changed the results from >33% chance of benefit to >60% chance of harm).

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE: In this retrospective analysis of data sets from patients with sepsis, 4 clinical phenotypes were identified that correlated with host-response patterns and clinical outcomes, and simulations suggested these phenotypes may help in understanding heterogeneity of treatment effects. Further research is needed to determine the utility of these phenotypes in clinical care and for informing trial design and interpretation.

Source: JAMA. 2019 May 19. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.5791. [Epub ahead of print]

GRANT OF THE MONTH

PI: Ron Poropatich

PI (Pitt): Michael Pinsky

PI (CMU): Artur Dubrawski

Title: TRAuma Care In a Rucksack: TRACIR

Description: The goal of “TRAuma Care In a Rucksack: TRACIR” is to develop artificial intelligence (AI) technologies enabling medical interventions that extend the “golden hour” for treating combat casualties and ensure an injured person’s survival for long medical evacuations. A multidisciplinary team of Pitt researchers and clinicians from emergency medicine, surgery, critical care and pulmonary fields will provide a wealth of real-world trauma data and medical algorithms that CMU roboticists and computer scientists will incorporate in the creation of a “hard and soft robotic suit” into which an injured person can be placed. Monitors embedded in the suit will assess the injury, and AI algorithms will guide the appropriate critical care interventions and robotically apply stabilizing treatments, such as intravenous fluids and medications.

Source: Department of Defense

Amount: $3.71 million Pitt contract; $3.5 million CMU contract